James Quintero, the Director of the Center for Local Governance at the Texas Public Policy Foundation, was kind enough to provide some detailed answers to questions I sent him about the municipal pension crisis in Dallas and other large Texas cities. My questions are in italics.

The Dallas police/fireman’s pension fund issue is generally described as stemming from the fund manager’s risky real estate speculation. Are there any additional structural problems that helped hasten that fund’s crisis?

When it comes to Texas’ public retirement systems, one of my greatest concerns is that there are other ticking time-bombs, like the DPFP, out there getting ready to explode. It’s not just Dallas’ pension plan that’s taken on excessive risk to chase high yield in a low-yield environment.

Setting aside the issue of risk for a moment, the DPFP, like most other public retirement systems around the state, suffers from a fundamental design flaw. That is, it’s based on the defined benefit (DB) system, which guarantees retirees a lifetime of monthly income irrespective of whether the pension fund has the money to make good on its promises or not. This kind of system is akin to an entitlement program, warts and all, and is very much at the heart of pension crises brewing in Texas and across the country.

One of the biggest problems with DB plans is that they rely on a lot of fuzzy math to make them work, or at least give the appearance of working. Take the issue of investment returns, for example. Many systems assume an overly optimistic rate of return when estimating a fund’s future earnings. Baking in these rosy projections is, among other things, a way to understate a plan’s pension debt. In an October 2016 study that I co-authored with the Mercatus Center’s Marc Joffe, I wrote the following to illustrate this very point:

For example, the Houston Firefighters’ Relief and Retirement Fund (HFRRF) calculates its pension liability using a long-term expected rate of return on pension plan investments of 8.5%. During fiscal year 2015, the plan’s investments returned just 1.53%. Over a 7- and 10-year period the rates of return were 6.4% and 7.9%, respectively. Not achieving these investment returns year-after-year can have a dramatic fiscal impact.

Even a small change in the actuarial assumptions can have major consequences for the fiscal health of a pension fund. According the HFRRF’s 2015 Comprehensive Annual Financial Report, a 1% decrease in the current assumed rate of return (8.5%) would almost double the fund’s pension liabilities, from $577.7 million to $989.5 million.

So while risky real estate deals were certainly a catalyst in the current unraveling of the DPFP, I suspect that its refusal to move away from the defined benefit model and into a more sustainable alternative—much like the private sector has already done—would have ultimately led us to this same point of fiscal crisis.

To what legal extent (if any) is Dallas police/fireman’s pension fund backstopped by the City of Dallas and/or Dallas County?

Let me preface this by saying that I’m not a lawyer nor do I ever intend to be one. However, Article XVI, Section 66 of the Texas Constitution plainly states that non-statewide retirement systems, like DPFP, and political subdivisions, like the city of Dallas, “are jointly responsible for ensuring that benefits under this section are not reduced or otherwise impaired” for vested employees. Given that, it’s hard to see how the city of Dallas—or better yet, the Dallas taxpayer—isn’t obligated in some major way when their local retirement system reaches the point of no return, which may be a lot closer than people think given all the lump-sum withdrawals of late.

Likewise, does the state of Texas have any statutory backstop to the Dallas police/fireman’s pension fund, or any other local pension funds?

For non-statewide plans, I don’t believe so. Again, I’m not a lawyer, but the Texas Attorney General wrote something fairly interesting recently touching on aspects of this question.

In September 2016, House Chairman Jim Murphy asked the AG to opine on “whether the State is required to assume liability when a local retirement system created pursuant to title 109 of the Texas Civil Statutes is unable to meet its financial obligations.” Title 109 refers to 13 local retirement systems in 7 major metropolitans that are a small-but-important group of plans that have embedded some of their provisions in state law (i.e. benefits, contribution rates, and composition of their boards) I’ve written a lot about this problem in the past (read more about it here).

In response to Chairman Murphy’s question, the AG had this to say:

In no instance does the constitution or the Legislature make the State liable for any shortfalls of a municipal retirement system regarding the system’s financial obligations under title 109. The Texas Constitution would in fact prohibit the State from assuming such liability without express authorization.

…a court would likely conclude that the State is not required to assume liability when a municipal retirement system created under title 109 is unable to meet its financial obligations.

So at least in the AG’s opinion, state taxpayers wouldn’t be required by law to bail out this subset of local retirement systems. But of course, the political calculus may be different than what’s required by law.

Compared to the Dallas situation, how badly off are the Houston, Austin and San Antonio public employee pension funds?

If you’re a taxpayer or property owner in one of Texas’ major cities, I’d be concerned. Moody’s, one of the largest credit rating agencies in the U.S., recently found that: “Rapid growth in unfunded liabilities over the past 10 years has transformed local governments’ balance sheet burdens to historically high levels,” and that Austin, Dallas, Houston, and San Antonio had a combined $22.6 billion in pension debt—and it’s growing worse!

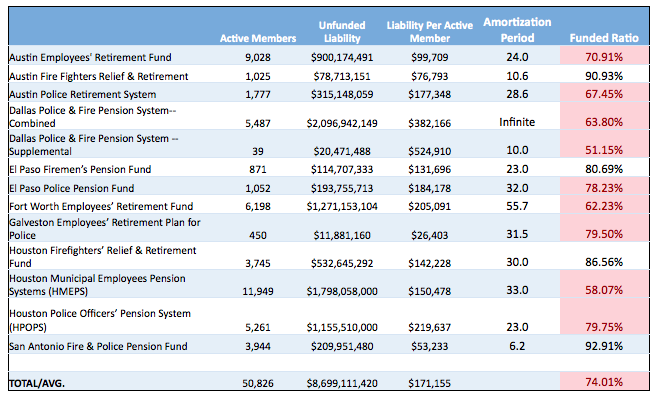

Using the Pension Review Board’s latest Actuarial Valuations Report for November 2016, we can parse the systems within each municipality to get a little bit better sense of where the trouble lies. Pension debt for the retirement systems in the big 4 looks like this:

Of course, it’s important to keep in mind that the figures use some of the same fuzzy math as described above, so the actual extent of the problem may be worse than the PRB’s latest figures indicate.

What similarities, if any, are there to current Texas municipal pension issues and those that forced California cities like San Bernardino, Stockton and Vallejo into bankruptcy? What differences?

The common element in most, if not all, of these systemic failures is the defined benefit pension plan. Because of the political element as well as the inclusion of inaccurate investment assumptions in the DB model, these plans are almost destined to fail, threatening the taxpayers who support it and the retirees who rely on it. And sadly, that’s what we’re witnessing now across the nation.

As far as the differences go, California’s municipal bankruptcies as well as Detroit’s were preceded by decades of poor fiscal policy and gross mismanagement. I don’t see that same thing here in Texas, but it’s also important that we don’t let it happen too.

California pensions were notoriously generous (20 years and out, spiking, etc.). Do any Texas state or local pensions strike you as unrealistically generous?

Any plan that’s making pension promises but has no plan on how to make good on those promises is being unrealistically generous. And unfortunately for taxpayers and retirees alike, a fair number of plans can be categorized as such.

The Pension Review Board’s Actuarial Valuations Report for November 2016 reveals that of Texas’ 92 state and local retirement system, only 4 of them are fully-funded. At the other extreme, a whopping 19 of the 92 plans have amortization periods of more than 40 years. Six of those 19 plans have infinite amortization periods, which effectively means that they have no plan to keep their promises but are instead planning to fail.

As far as specific plans go, there’s no question that the Dallas Police and Fire Pension System is the posterchild for the overly generous. The Dallas Morning News recently covered the surreal levels of deferred compensation offered, finding that:

The lump-sum withdrawals come from the Deferred Retirement Option Plan, known as DROP. The plan allows veteran officers and firefighters to essentially retire in the eyes of the system and stay on the job.

Their benefit checks then accrue in DROP accounts. For years, the fund guaranteed interest rates of at least 8 percent. DROP made hundreds of retired officers and firefighters millionaires. And once they stopped deferring the money, they received their monthly benefit checks in addition to their DROP balance. [emphasis mine]

It’s probably fair to say that any public program that makes millionaires out of its participants is probably being too generous with its benefits.

There seem to be only two recent local government bankruptcies in Texas, neither of which were by cities: Hardeman County Hospital District Bankruptcy and Grimes County MUD #1. Did either of these involve pension debt issues?

I’m not familiar with those instances, but when it comes to the issue of soaring pension obligations, I can tell you that the system as a whole is moving in bad direction.

In November 2016, Texas’ 92 state and local retirement systems had racked up over $63 billion dollars of unfunded liabilities, with more than half owed by the Teacher Retirement System. That’s a staggering amount of pension debt that’s not only big but growing fast. And worse yet, that’s in addition to Texas’ already supersized local government debt-load.

How we’re going to make good on all of these unfunded pension promises is anyone’s guess. But I imagine that it’ll involve some combination of much higher taxes, benefit reductions, and fewer city services.

What limits or constraints does Texas place on Chapter 9 bankruptcy?

The Pew Charitable Trusts’ Stateline has some good information on this, at least as far as municipal bankruptcy is concerned. A November 2011 report, Municipal Bankruptcy Explained: What it Means to File for Chapter 9, had this to say about the process:

Who can file for Chapter 9? Only municipalities — not states — can file for Chapter 9. To be legally eligible, municipalities must be insolvent, have made a good-faith attempt to negotiate a settlement with their creditors and be willing to devise a plan to resolve their debts. They also need permission from their state government. Fifteen states have laws granting their municipalities the right to file for Chapter 9 protection on their own, according to James Spiotto, a bankruptcy specialist with the Chicago law firm of Chapman and Cutler. Those states are Alabama, Arizona, Arkansas, California, Idaho, Kentucky, Minnesota, Missouri, Montana, Nebraska, New York, Oklahoma, South Carolina, Texas and Washington.

Hopefully this is a process that can be avoided entirely, but given the fiscal condition of the DPFP and potentially a few other systems, I’m not sure that’ll be the case.

Next to Dallas, which municipal pensions would you say are in the worst shape?

I’m most concerned about the local retirement systems in Title 109. The reason, again, is that these 13 local retirement systems are effectively locked into state law and there’s little that taxpayers or retirees in those communities can do to affect good government changes without first going to Austin. These systems have basically taken a bad situation and made it worse by fossilizing everything that counts.

In the Texas Public Policy Foundation’s 2017-18 Legislator’s Guide to the Issues, I cover this issue in a little more detail. In the article (see pgs. 122 – 124), I write of these plans’ fiscal issues which can be seen below, albeit with slightly older data.

(Funded ratios marked in red denote systems that are below the 80% threshold, signifying a plan that may be considered actuarially unsound. Source: Texas Bond Review Board.)

The fact that these systems either are in or are headed for fiscal muck is a big reason why the Texas Public Policy Foundation is helping to educate and engage on legislation that would restore local control of these state-governed pension plans. People on the ground-level should have some say over their local plans, and that’s what we’ll be fighting for next session. Encouragingly, a bill’s already been filed in the Senate (see SB 152) and there should be legislation filed shortly in the House to do just that.

Should Texas government agencies switched over to defined contribution (i.e. 401K) plans over standard pension plan, and if so, how might this realistically be accomplished without endangering existing retirees?

ABSOLUTELY. Ending the defined benefit model and transitioning new employees into something more sustainable and affordable, like a defined contribution system, is one of the best things that the state legislature can do. This is something I’ve long been an advocate of.

In fact, in early 2011, I played a very minor role in the publication of some major research spearheaded by Dr. Arthur Laffer, President Ronald Reagan’s chief economist, that advanced this same reform idea (see Reforming Texas’ State & Local Pension Systems for the 21st Century). I’ve also written a lot about the need to make the DC-switch, making the case recently in Forbes that:

DC-style plans resemble 401(k)s in the private sector and the optional retirement programs (ORP) available for higher education employees in Texas. These DC-style plans put the power of an individual’s future in their own hands instead of depending on the good fortune of government-directed DB-style plans. DC-style plans are portable and sustainable over the long term as they are based on the contributions of retirees and a defined government match.

With DC-style plans, retirees will finally have the opportunity to determine how much risk they are willing to take. They also reduce the risk that the government will default on their retirement or fund those losses with dollars from taxpayers who never intended to use these pensions. By giving retirees more freedom on how to best provide for their family, they will be in a much better position to prosper.

Because of their efficiency, simplicity and fully funded nature, the private sector moved primarily to DC-style plans long ago. For the sake of taxpayers and retirees dependent on government pensions, it’s time for all governments to move to these types of plans as well.

As far as dealing with transition costs, some much smarter people than I have written on this issue and found that it’s not as big of a challenge as it’s made out to be. Dr. Josh McGee, a vice president with the Laura and John Arnold Foundation, a senior fellow with the Manhattan Institute, and Chairman of the Pension Review Board, had this to say about the matter:

Moving to a new system would have little to no effect on the current system. State and local pensions are pre-funded systems, and unlike Social Security, the contributions of workers today do not subsidize today’s retirees. Future normal cost contributions are used to fund new benefit accruals that workers earn on a go-forward basis and are not used to close funding gaps. Therefore, it matters little whether the normal cost payments are used to fund new benefits under the current system or a new system.

(Source: The transition cost mirage—false arguments distract from real pension reform debates.)

Another pension expert, Dr. Andrew Biggs with the American Enterprise Institute, published research that found that:

In this study, I show that if a pension plan were closed to new hires, over time the duration of liabilities would shorten, and the portfolio used to fund those liabilities would become more conservative. However, the effects of these transition costs are so small as to be barely perceptible.

(Source: Are there transition costs to closing a public-employee retirement plan?)

I’m confident that with the right plan in place, Texas’ state and local retirement systems can make the switch to defined contribution and we’ll be all the better for it.

Thanks to James Quintero for providing such a detailed analysis!

And since we’re on the topic, here’s a roundup of news on the Dallas Police and Fireman’s pension fund crisis:

Dallas created the police and fire plan in 1916. The system’s trustees eventually persuaded the state legislature to allow employees and pensioners to run the plan. Not surprisingly, the members have done so for their own benefit and sent the tab for unfunded promises—now estimated at perhaps $5 billion—to taxpayers. Among the features of the system is an annual, 4 percent cost-of-living adjustment that far exceeds the actual increase in inflation since 1989, when it was instituted. A Dallas employee with a $2,000 monthly pension in 1989 would receive $3,900 today if the system’s annual increases were pegged to the consumer price index. Under the generous Dallas formula, however, that same monthly pension could be worth more than $5,000. No wonder the ship is sinking.

The system also features a lavish deferment option that lets employees collect pensions even as they continue to work and earn a salary. Moreover, the retirement money gets deposited into an account that earns guaranteed interest. Governments originally began creating these so-called DROP plans as an incentive to encourage experienced employees to keep working past retirement age, which in job categories like public safety can be as young as 50. In Dallas, the pension system gives workers in the DROP plan an 8 percent interest rate on their cash, at a time when yields on ten-year U.S. Treasury notes, a standard for guaranteed returns, are stuck at less than 2 percent. According to the city, some 500 employees working past retirement age have accumulated more than $1 million in these accounts—on top of the pensions that they will receive once they officially stop working.

Over the years, the Dallas Police and Fire Pension System fund has amassed $2 billion to $5 billion in unfunded liabilities, the result of bad real estate investments and blatant self-enrichment from prior management. Coupled with a possible setback in ongoing litigation over public safety salaries, Dallas is in the most financially precarious position in its history.

City officials are openly uttering the word bankruptcy, not just of the pension fund but the city itself. As Mayor Mike Rawlings told the Texas Pension Review Board this month, “the city is potentially walking into the fan blades that might look like bankruptcy.”

The state Legislature created this mess by not giving the city a meaningful voice in the fund’s operation and allowing the former board of the pension fund to unilaterally sweeten its membership’s promised benefits without concern to the overall fiscal damage being done. Now it must help the city clean up the mess.

Dallas already provides nearly 60 percent of its budget to support public safety services and recently contributed $4.6 million to increase its share of pension contributions to 28.5 percent — the maximum allowed under state statute. However, if Dallas loses the lawsuit over salaries and no changes are made to the pension fund, the city could take an $8 billion hit. That is roughly equal to eight years of the city’s general fund budget.

Austin, Dallas, Houston and San Antonio collectively face $22.6 billion worth of pension fund shortfalls, according to a new report from credit rating and financial analysis firm Moody’s. That company analyzed the nation’s most debt-burdened local governments and ranked them based on how big the looming pension shortfalls are compared to the annual revenues on which each entity operates.

“Rapid growth in unfunded pension liabilities over the past 10 years has transformed local governments’ balance sheet burdens to historically high levels,” the report says.

Chicago had the most dire ratio on the national list. Dallas came in second. According to the report, the North Texas city has unfunded pension liabilities totaling $7.6 billion. That’s more than five times the size of the city’s 2015 operating revenues.

Both those cities may turn to the public to partially shore up their shortfalls. Houston Mayor Sylvester Turner wants to use $1 billion in bonds to infuse that city’s funds. Dallas police officer and firefighter pension officials also want $1 billion from City Hall, an amount officials there say is too high.

Meanwhile, Austin ranked 14th on the Moody’s list with unfunded pension liabilities of $2.7 billion. San Antonio ranked 22nd with a $2.3 billion shortfall.