The last three days of combat should put a serious dent in the reputation of this new Russian army. We should, however, try to understand why the Russians are struggling. First, the Russian army’s recent structural reforms do not appear to have been sufficient to the task at hand. Second, at the tactical and operational level, the Russians are failing to get the most out of their manpower and materiel advantage.

There has been much talk over the last ten years about the Russian army’s modernization and professionalization. After suffering severe neglect in the ’90s, during Russia’s post-Soviet financial crisis, the army began to reorganize and modernize with the strengthening of the Russian economy under Putin. First the army got smaller, at least compared to the Soviet Red Army, which allowed a higher per-soldier funding ratio than in previous eras. The Russians spent vast sums of money to modernize and improve their equipment and kit — everything from new models of main battle tanks to, in 2013, ordering Russian troopers to finally retire the traditional portyanki foot wraps and switch to socks.

But the Russians have also gone the wrong direction in some areas. In 2008, the Russian government cut the conscription term from 24 to twelve months. As Gil Barndollar, a former U.S. Marine infantry officer, wrote in 2020:

Russia currently fields an active-duty military of just under 1 million men. Of this force, approximately 260,000 are conscripts and 410,000 are contract soldiers (kontraktniki). The shortened 12-month conscript term provides at most five months of utilization time for these servicemen. Conscripts remain about a quarter of the force even in elite commando (spetsnaz) units.

As anyone who has served in the military will tell you, twelve months is barely enough time to become proficient at simply being a rifleman. It’s nowhere near enough time for the average soldier to learn the skills required to be an effective small-unit leader.

Yes, the Russians have indeed made efforts to professionalize the officer and the NCO corps. Of course, non-commissioned officers (NCOs) have historically been a weakness of the Russian system. In the West, NCOs are the professional, experienced backbone of an army. They are expected to be experts in their military speciality (armor, mortars, infantry, logistics, etc.) and can thus be effective small-unit commanders at the squad and section level, as well as advisers to the commanders at the platoon and company level. In short, a Western army pairs a young infantry lieutenant with a grizzled staff sergeant; a U.S. Marine Corps company commander, usually a captain, will be paired with a gunnery sergeant and a first sergeant. The officer still holds the moral and legal authority and responsibility for his command — but he would be foolish to not listen to the advice and opinion of the unit’s senior NCOs.

The Russian army, in practice, does not operate like this. A high proportion of the soldiers wearing NCO stripes in the modern Russian army are little more than senior conscripts near the end of their term of service. In recent years, the Russians have established a dedicated NCO academy and cut the number of officers in the army in an effort to put more resources into improving the NCO corps, but the changes have not been enough to solve the army’s leadership deficit.

Now, let’s talk about the Russian failures at the operational and tactical level.

It should be emphasized again that the Russian army, through sheer weight of men and materiel, is still likely to win this war. But it’s becoming more and more apparent that the Russians’ operational and tactical choices have not made that task easy on themselves.

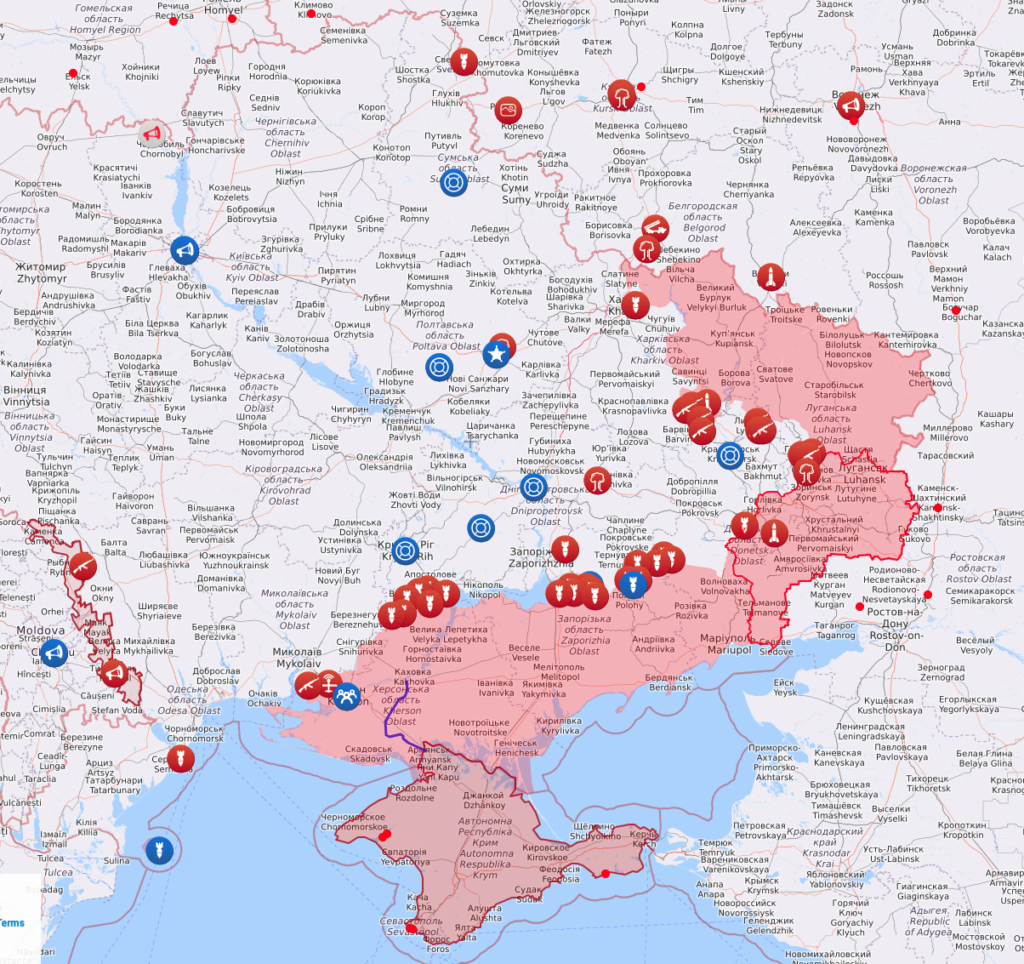

First, to many observers, it’s simply shocking that the Russians have not been able to establish complete air superiority over Ukrainian air space. After three days of hostilities, Ukrainian pilots are still taking to the skies and Ukrainian anti-air batteries are still exacting a toll on Russian aircraft. The fact that the Russians have not been able to mount a dominant Suppression of Enemy Air Defenses (SEAD) campaign and yet are insistent on attempting contested air-assault operations is, simply put, astounding. It’s also been extremely costly for the Russians.

To compound that problem, the Russians have undertaken operations on multiple avenues of advance, which, at least in the early stages of this campaign, are not able to mutually support each other. Until they get much closer to the capital, the Russian units moving north out of Crimea are not able to help the Russian armored columns advancing on Kyiv. The troops pushing towards Kyiv from Belarus aren’t able to affect the Ukrainians defending the Donbas in the east. As the Russians move deeper into Ukraine, this can and will change, but it unquestionably made the opening stages of their operations more difficult.

Third, the Russians — possibly out of hubris — do not appear to have prepared the logistical train necessary to keep some of their units in action for an extended period of time. Multiple videos have emerged of Russian columns out of gas and stuck on Ukrainian roads.

The classic saying is “Amateurs talk about tactics, but professionals study logistics” (attributed to Marines Corps commander Gen. Robert H. Barrow, but I suspect the general sentiment is much older). An army runs on its stomach, and a modern mechanized army runs on its gas tank, and something has clearly gone wrong in with Russian logistical support for this war.

(@NoYardstick)

(@NoYardstick)