Before we turn our attention to North Korea, there’s still the war against the Islamic State to be won. And there’s lots of significant news there.

Before launching the battle to capture Islamic State’s de facto capital, the U.S.-led military coalition dropped leaflets calling on extremists to surrender. On the ground, militants were going door to door, demanding that residents pay their utility bills.

Islamic State, long bent on expanding its religious empire with shocking brutality in the form of public executions, crucifixions and whippings, is desperately focused on its own survival.

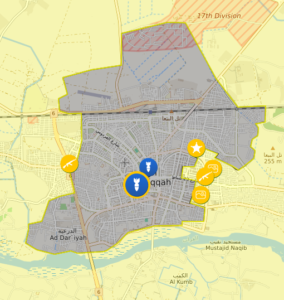

Raqqa has been a crucial part of the terror group’s self-declared caliphate. Until a few months ago, public squares were lined with decomposing bodies of those who had run afoul of Islamic State’s religious rules or bureaucracy.

Instead of ruthlessly enforcing no-smoking decrees and dress codes, though, militants now are doing whatever they can to hold on to areas still controlled by the group—and revenue needed to help keep Islamic State afloat financially.

They are so preoccupied that some women in Raqqa dare to uncover their faces in public. A few men defiantly smoke in the streets and shave their beards, current and former residents say.

When the call to prayer sounds from mosques, some residents no longer bother to go. Islamic State used to force shops to close and people to pray.

Women accused of violating Islamic State’s strict dress code were once whipped. In May, though, militants released two women unharmed after they were forced to buy new robes and all-covering face veils sold by Islamic State’s religious police for 10,000 Syrian pounds each, or a total of about $40, says Dalaal Muhammad, a sister and aunt of the women.

Ms. Muhammad, 37 years old, says her sister had to beg a family member to borrow the $40 from friends.

“They didn’t even have enough to buy bread,” she said at a camp for displaced Syrians, wearing sandals held together by twine. “They just wanted to get the money quickly because we were running out of time” to flee Raqqa.

An estimated 25,000 civilians remain trapped in Raqqa under Islamic State control, according to the United Nations, and more than 230,000 people have fled Raqqa and its suburbs since early April. On Thursday, the U.N. called for a pause in the assault so civilians can escape.

Fighters for the U.S.-backed Syrian Democratic Forces, which is leading the assault to oust Islamic State from Raqqa, say on some days they have helped dozens of civilians reach safety. Other days, no one makes it out. Militants execute smugglers helping civilians flee and those accused of collaborating with the U.S.-led coalition.

The Pentagon has estimated there are fewer than 2,500 Islamic State militants left in the city, down from about 4,500.

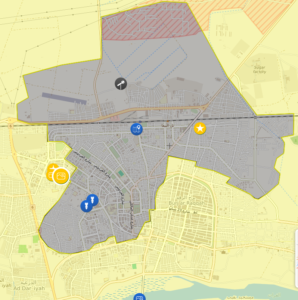

Militants spent months girding for the long-anticipated assault before it began in June. They dug extensive tunnels beneath streets and homes, set up snipers’ nests and planted improvised explosive devices everywhere to stop people from fleeing.

“They wanted us as human shields,” says Obaida Matraan, 33 years old, a taxi driver who escaped with his family one night just before the battle began. They carried a piece of white fabric to wave as they approached the SDF.

Before the escape, he saw on public display the bodies of executed men with signs that said “smuggler” as “a warning to others,” recalls Mr. Matraan.

In early 2014, Raqqa was the first city in Syria or Iraq to fall under Islamic State’s complete control. The group has lost about 60% of the territory it held in January 2015, including its former Iraqi stronghold of Mosul, according to analysts at IHS Markit Ltd.’s Conflict Monitor.

Even as the self-declared caliphate crumbles, Islamic State has continued to claim responsibility for deadly terror attacks around the world, including in Spain last week, in a bid to project power.

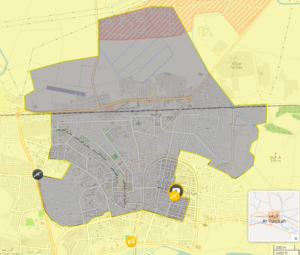

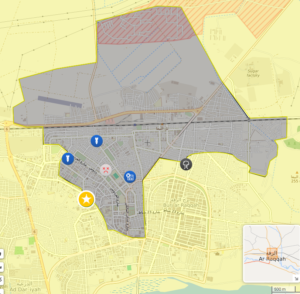

The SDF has encircled Raqqa and says it has seized more than half the area of the city. But militants are capable of striking behind the coalition’s front lines and are scrambling to hoard the little food and water left in areas they control. Much of Raqqa remains a battlefield.

The ground advance by the SDF has been aided by coalition airstrikes. At least 465 civilians have likely been killed in those airstrikes since the battle began, independent monitoring group Airwars reported.

The U.S.-led coalition said it investigates civilian casualties. Monthly reports released by the coalition show far lower estimates of civilian casualties.

Syrian activist groups estimate that at least dozens more civilians were killed during the past week. Civilians still in Raqqa say the airstrikes seem indiscriminate and kill more civilians than militants, who hide out in tunnels.

At the height of Islamic State’s control, life in Raqqa and elsewhere in the group’s territory was dictated by so many laws on everyday life that residents struggled to keep track of them.

Banned items ranged from men’s skinny jeans (too Western and provocative) to canned mushrooms (made with preservatives) to bologna (because the group said it contained pork).

Enforcement slackened as the Syrian Democratic Forces advanced toward Raqqa through the Syrian countryside and eventually surrounded the city, according to residents who fled recently.

Checkpoints thinned out as Islamic State leaders and many militant fighters abandoned the city and headed to the eastern province of Deir Ezzour, residents said. The group still holds much territory in the oil-rich region and is expected to make its last stand there.

People who have left Raqqa say militants suddenly seemed to care much more about money than morals. Islamic State’s revenue—from oil production and smuggling, taxation and confiscation, and kidnapping ransoms—is down 80% in the past two years, IHS Conflict Monitor estimates.

For months, Islamic State ordered businesses and residents to use only the caliphate’s own currency of gold and silver coins, current and former residents said. The move forced people to trade in their U.S. dollars and Syrian pounds to Islamic State, which wanted those currencies as its territory shrinks.

Mr. Matraan, the taxi driver, says Islamic State made him pay $30 for water, electricity and a landline telephone bill just weeks before his family fled.

“They would go to people’s homes and demand payment,” said Mr. Matraan, who wore a San Jose Sharks cap under the searing sun at a camp for displaced Syrians in Ain Issa, a city north of Raqqa. “In the end, their main concern was money.”

Abdulmajeed Omar, 27, says militants began fining those caught violating Islamic State’s smoking ban, rather than jailing or whipping them. Being caught with a pack of cigarettes brought a $25 fine. The fine for a carton of cigarettes was $150.

“They didn’t bother with poor people,” says Mr. Omar, who fled Raqqa before the battle and returned with the Kurdish YPG militia to fight Islamic State.

Before Ms. Muhammad fled the city, militants spent a month digging a tunnel underneath her home in the eastern neighborhood of al-Mashlab, she said. Like many of her neighbors, Ms. Muhammad was afraid to ask them what they were doing.

Inside one house in al-Mashlab, which has since been captured by SDF forces, a tunnel opening cut through the living-room floor. The fighters filled the hole with broken furniture because they weren’t sure where the tunnel led.

“We are suffering from snipers and tunnels,” said Dirghash, a Kurdish YPG commander on the city’s eastern front line who wouldn’t give his last name. “The tunnels are all in civilian homes, and we suddenly find [Islamic State militants] popping up behind us.”

On the western side of Raqqa, a warning painted in silver on the metal shutters of a motorcycle shop simply read: “There are mines.”

In captured neighborhoods, the walls already are covered with new graffiti by the YPG, the Syrian Kurdish militia that is the dominant group in the Syrian Defense Forces. Every conquering force that has swept through Raqqa since the Syrian conflict began more than six years ago has left its mark with cans of paint.

Assuming both Deir ez-Zor and Raqqa both fall this month, the Islamic State is left with very little viable territory in Syria, mainly a populated strip along the Euphrates from Al Busayrah to Abu Kamal on the Iraqi border, which is some 63 miles or so.

In Iraq, U.S.-supported forces also continue to make gains against the Islamic state, including the liberation of Tal Afar at the end of August. “The Iraqi forces killed over 2,000 Islamic State (IS) militants and more than 50 suicide bombers during a major offensive to free Tal Afar area in west of Mosul, officials said.” The operation is described as a “blitzkrieg” rather than the grinding urban warfare that characterized the Battle of Mosul.