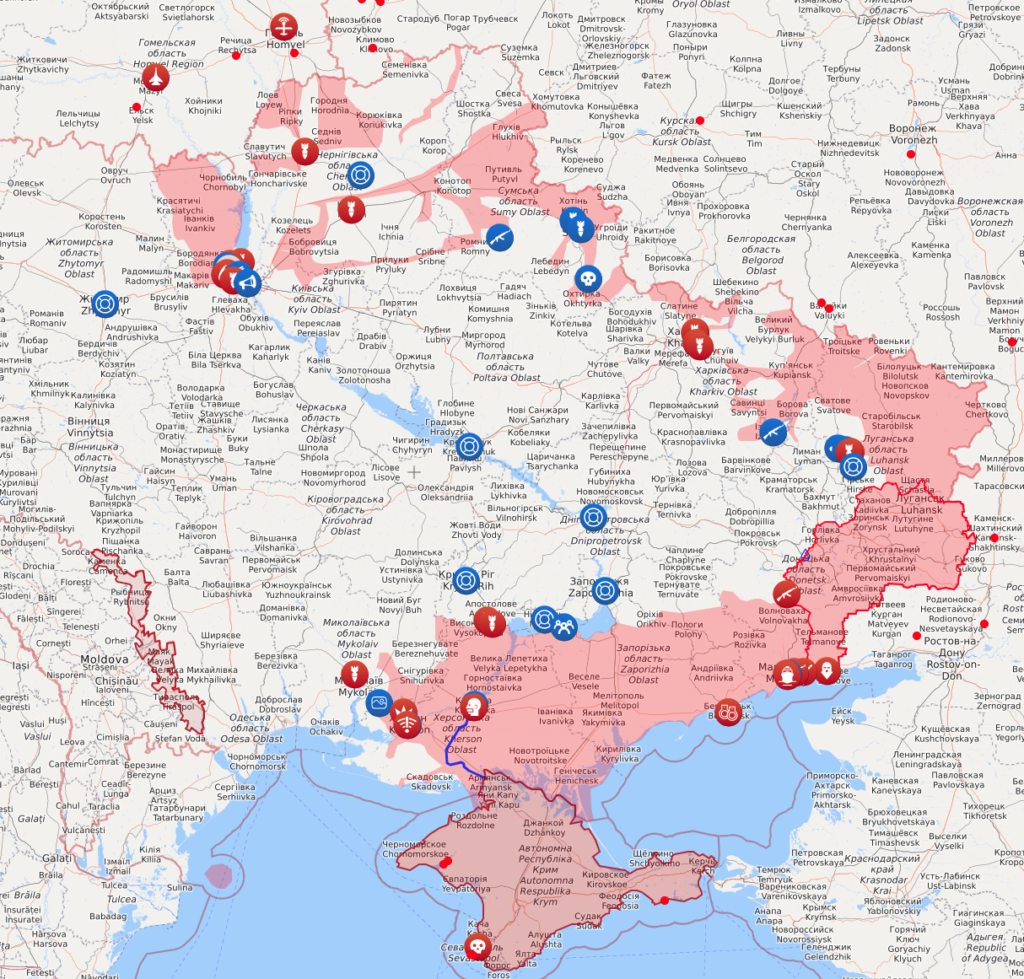

There’s just enough tank-specific news coming out of the Russo-Ukrainian War to justify a roundup. Despite supposedly having the largest tank army in the world, Russia’s tank corps is clearly taking it on the chin in Ukraine.

#Russia's active tank fleet is actually not 12,000 strong. In reality it is just over 2,500. By active tanks I mean tanks that are actually in service in an organised unit (i.e. a tank battalion, regiment, brigade etc.) and are not undergoing field tests (T-14 Armata). pic.twitter.com/fJYrGjc5L4

— TankDiary (@TankDiary) March 19, 2022

Can Russia pull reserve tanks out of its inventory and put them in active duty? Probably, but: A.) The truck tire issued showed that even active equipment hasn’t been well-maintained. How much worse shape are mothballed vehicles in? B.) How quickly can new tank crews be trained to work effectively? Speaking of maintenance problems:

Russia’s largest tank manufacturer, Uralvagonzavod, has halted production because of supply shortages, according to Ukraine’s state media and Ukrainian armed forces.

The Kyiv Independent writes that Uralvagonzavod has stopped operations in its Chelyabinsk Tractor Plant in west-central Russia because of the lack of component parts supplied from foreign countries.

The claim was initially made by a report of the Armed Forces of Ukraine and confirmed by the Ukrainian Ministry of Defense on March 21, according to The Kyiv Independent.

Uralvagonzavod had his assets frozen in the U.K. on February 24 and was hit by European Union sanctions on March 15.

Two reasons to take this with a few grains of salt: A.) It’s a Ukrainian source, and B.) Uralvagonzavod is the company manufacturing the T-14 Armata tank as well as the T-90M, and they were only supposed to produce 100 T-14s total, of which none have been spotted in-theater.

A LOT OF Russian tanks involved in the invasion of Ukraine have strange cages welded over the roofs of their turrets. Strange and apparently useless—for many pictures have emerged of destroyed vehicles surmounted by them. Sometimes the cage itself has been visibly damaged by an attack that went on to hit the tank beneath.

Stijn Mitzer, an independent analyst based in Amsterdam, has looked at hundreds of verified photographs of destroyed Russian vehicles. He thinks that, far from acting as protection, the cages have done nothing save add weight, make tanks easier to spot, and perhaps give a false and dangerous sense of security to the crew inside. They have thus been mockingly dubbed by some Western analysts as “emotional-support armour” or “cope cages”.

Snip.

The new cages, the fitting of which seems to have begun late in 2021, appear to be a variant of so-called slat or bar armour. Such armour can provide effective lightweight protection if used correctly (as it is, for example, on American Stryker armoured personnel carriers). But in this case that seems not to have happened. They might thus be seen as symbols of Russia’s inadequate preparation for the campaign, as pertinent in their way as its failures to neutralise Ukraine’s air defences and to shoot down that country’s drones.

One of the main threats to armoured vehicles are HEAT (High Explosive Anti-Tank) weapons, such as the Russian-made but widely employed RPG-7. The warheads of these rocket-propelled grenades are shaped charges—hollow cones of explosive lined with metal. When the explosive detonates it blasts the metal lining into a narrow, high-speed jet that is able to punch through thick steel. According to Dr Appleby-Thomas an RPG-7 can penetrate 30cm of steel plate.

And RPG-7s are the babies of the bunch. Other, far more powerful shaped-charge anti-tank weapons used by Ukrainian forces include Javelins supplied by America, NLAWs (Next-generation Light Anti-tank Weapons) supplied by Britain, and drone-borne MAM-L missiles, supplied by Turkey.

HEAT warheads may be countered by what is known as explosive reactive armour, or ERA. When this is hit, a sheet of explosive sandwiched inside it blows up and disrupts an incoming warhead before it can detonate. Many Russian tanks are indeed fitted with ERA. However ERA may, in turn, be defeated by a so-called tandem warhead, in which a small precursor charge triggers the armour’s explosive before the main warhead detonates.

Slat and bar add-on armours are a lighter and cheaper way to counter RPGs, though even if used correctly they are, literally, hit or miss protection. The spacing of the bars or slats is crucial. If a rocket hits a bar it makes little difference, for its warhead will detonate anyway. But if it gets trapped between bars it will probably be damaged in a way which means that the signal from the nose-mounted fuse cannot reach the detonator.

This approach is known as statistical armour, because the protection it offers is all or nothing. It is typically quoted as having a 50% chance of disrupting an incoming RPG. But Dr Appleby-Thomas notes that it works only against munitions with a nose fuse, which Javelins, NLAWs and MAM-Ls do not have.

Russia has been fitting slat armour to vehicles since 2016, but the design of the new cages, seemingly improvised from locally available materials, is baffling. They appear to be oriented in a way that protects only against attacks from above. In principle, that might help against Javelins, which have a “top attack” mode in which they first veer upwards and then dive to punch through a tank’s thin top armour. But, as Nick Reynolds, a land-warfare research analyst at RUSI, a British defence think-tank, notes, even if the cage sets off a Javelin’s precursor warhead, the main charge is still more than powerful enough to punch through the top armour and destroy the tank—as the Ukrainian army itself proved in December, when it tested one against a vehicle protected by add-on armour replicating the Russian design. As expected, the Javelin destroyed the target easily.

Enjoy this Sad Trombone gif, unearthed from the archives of the ancient, terrible conflict known only as The Pony Wars

Despite amassing an invasion force of nearly 200,000 troops and thousands of armored vehicles supported by combat aircraft and warships, the Russian military has failed to reach its primary objectives in the three weeks since its offensive into Ukraine began.

Russian military planners expected a blitzkrieg campaign that would last 48 to 72 hours and lead to a quick Ukrainian capitulation, but Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelenskyy has led a fierce resistance, and major urban centers, including the capital, Kyiv, remain in Ukrainian hands, surprising Moscow and indeed the world.

Ukrainians’ grit and knowledge of the battlefield have played a large part in their effective defense, but weapons supplied by NATO and EU countries have also played a critical role in stalling the Russian advance.

Ukraine has received billions of worth of weapons from the West — the US has provided $1 billion in security assistance just this week — and among that aid, three weapon systems stand out.

Since the invasion began, US-made FGM-148 Javelins and FIM-92 Stingers and the Next Generation Light Anti-Tank Weapon (NLAW) designed by Britain and Sweden have been the terror of Russian troops.

Tanks and armored vehicles are at the heart of the Russian military doctrine.

Actually Russian military doctrine is usually described as artillary-centric, but tanks are a close second in importance.

Russia’s battalion tactical groups — 75% of which have been committed to the invasion, a US official said Wednesday — are largely mechanized formations meant to use heavy firepower to overcome resistance.

But BTGs are vulnerable to anti-tank defenses like the Javelin, a reusable, fire-and-forget guided missile.

Javelins have two parts: a launch tube and a command launch unit, which has the controls and optical sights for day and night use. The Javelin missile’s nose has a homing infrared guidance system that allows the operator to fire the weapon and then relocate in order to dodge return fire.

Snip.

Against a tank or another armored vehicle, the Javelin will strike from a high angle of attack, targeting the top of the vehicle, where the armor is thinnest.

Before the invasion, Russian tankers sought to counter that by building cages on top of their tanks to detonate the Javelin before it struck and reduce its force. Hundreds of destroyed Russian tanks suggest that has not been an effective countermeasure.

Against a stationary target, like a building or bunker, the Javelin will strike from a more direct line of attack.

Snip.

Ukrainian forces have been using the British-supplied NLAW anti-tank weapon. Although less sophisticated than its American counterpart, the NLAW is extremely easy to operate, and with a 150 mm high explosive anti-tank warhead, it’s deadly too.

Like the Javelin, the NLAW can strike targets from above, but its effective range of about 800 meters is more limited than the Javelin’s 2,000-meter range.

Information on Stinger use against Russian aircraft snipped.

The US on Wednesday announced another package of security assistance to Ukraine, which included 800 Stingers and 2,000 Javelins, bringing the total of each provided by the US to 1,400 and 4,600, respectively. The package also includes 1,000 light anti-armor weapons and 6,000 AT-4 unguided, man-portable anti-armor missiles.

The Russian military’s one-off T-80UM2 experimental main battle tank has been knocked out during recent fighting in Ukraine, marking one of the more unusual kills attributed to the country’s defenders, who continue to disrupt the Kremlin’s invasion plans. The fact that this unique fighting vehicle was even participating in combat in Ukraine is somewhat surprising, but it would not be the first example of new or experimental Russian weapons systems being deployed in the campaign.

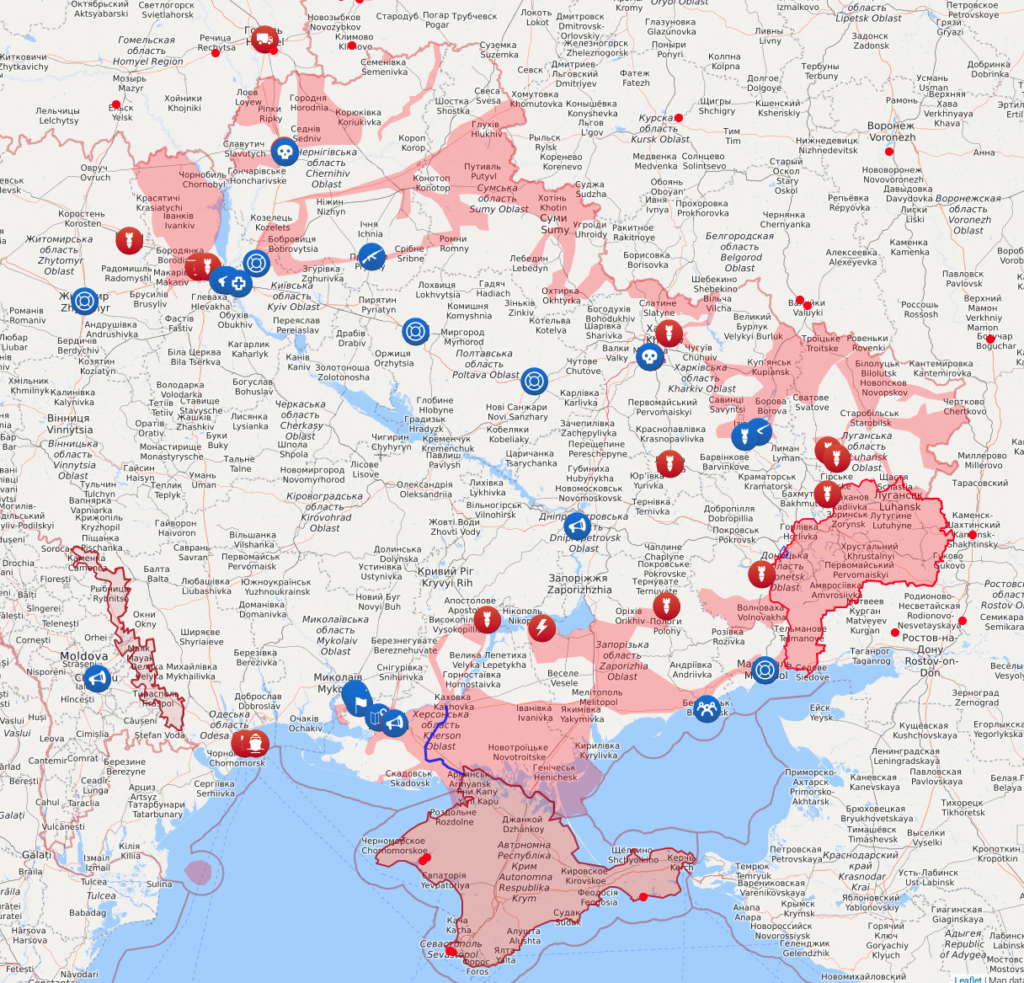

The team of researchers at the Oryx blog, who have been compiling photo and video evidence of materiel losses on both sides of the conflict, identified the wreckage of the T-80UM2 and stated that it was destroyed on March 17, or that its remains were uncovered on this date. The tank is rumored to have been knocked out in Sumy Oblast, in northeastern Ukraine, apparently in the vicinity of the town of Trostyanets.

The T-80UM2 is said to have been part of a larger column of Russian vehicles that came under attack by the Ukrainian Armed Forces and photos show destroyed trucks alongside the T-80UM2. Its turret was knocked off and its hull burnt out, although it’s not immediately clear how it was hit and by what.

The story of the T-80UM2 is a complicated one, tied up with a new-generation tank project with the project name Objekt 640, better known as the Black Eagle. A mock-up of the Black Eagle appeared as long ago as 1997, at which point it was being promoted for the export market.

By 1998 it had become clear that work was also underway on the T-80UM2, as a further development of the Cold War-era T-80. There seems to be substantial overlap between the T-80UM2 and the Black Eagle, to the point that some sources consider them one and the same. If that’s the case, then the T-80UM2 may very well have been intended to serve as a prototype for the Black Eagle which, as it turned out, never entered production.

As for the T-80UM2, this vehicle was based on an upgraded T-80U chassis, the main new addition being a welded-steel turret with advanced armor protection, including Kaktus explosive reactive armor (ERA), panels of which were also applied to the front of the hull. More Kaktus was fitted to the track skirts, while there were anti-fragmentation screens around the front of the turret.

In its ultimate form, the T-80UM2 was also fitted with the Drozd-2 active protection system, a hard-kill system that uses radar to detect incoming anti-tank rockets and anti-tank missiles, before automatically firing high-explosive fragmentation munitions at them, with the aim of destroying, or at last disabling them, at a distance of 20-30 feet from the tank.

The T-80UM2 featured a different crew arrangement compared to the T-80U, with the gunner seated on the right and the commander on the left of the turret, swapping sides compared to the earlier tank.

Otherwise, the new tank used the same main armament as the earlier T-80 series, with a 125mm 2A45M smoothbore gun, but this was now fed ammunition via an improved type of automatic loading system. The magazine was moved from below the turret to the bustle, at the back of the turret, apparently in response to survivability concerns highlighted during fighting in Chechnya.

In western armies, prototypes are rarely pressed into combat service, they’re generally preserved in tank museums (like Tortoise at Bovington or the T-28 at the Patton Museum of Cavalry and Armor). The fact that this one was pressed into frontline service may suggest a whiff of desperation to throw everything into the fight. Then again, the Russian military has never been known for being overly sentimental…